I don’t have a fear of flying. I fly a lot. But every time the plane hits turbulence I get a niggling feeling in the back of my mind that maybe this could be the end. The plane will crash, and we will all die.

Logically, I know turbulence is just down to the movement of air and is very unlikely to cause a plane to fall out of the sky. But my illogical mind usually takes over and I find myself contemplating my own mortality.

It’s similar to the feeling I remember having when the stockmarket plummeted on 20 March 2020, courtesy of the Covid pandemic, and my inherited Lloyds shares lost half their value overnight.

The adviser has to be like a psychologist and therapist

My immediate reaction was to sell — and that would, logically, have been the worst possible thing to do with them. But, again, my illogical mind nearly took over.

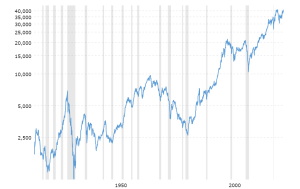

Luckily, my parents’ financial adviser forcefully suggested that selling would be a stupid thing to do, and showed me one of those graphs that illustrate market movements through history (see example below).

It helped because it demonstrated how, over time, markets will always rise. Even the frightening fall caused by the Covid pandemic now looks like a small blip on the graph.

Graph: Dow Jones 100-year historical chart

Source: Macrotrends

Since I joined Money Marketing in 2021, I’ve spoken to a lot of financial advisers, so I know I’m not the only one to react in that fashion when markets drop. It seems to be the most common response. Psychologically, it makes sense: things are bad, so you want out.

Global jitters

And times are certainly volatile right now.

Last month, stockmarkets around the world took sizeable falls amid fears that the US might be heading for a recession.

The FTSE 100 dropped 3.05%, while the FTSE 250 experienced its biggest fall since former prime minister Liz Truss’s Mini-Budget in September 2022 (4.07%).

People don’t want to just accumulate wealth. They want to be OK, and know their kids will be OK

Meanwhile, the US S&P 500 fell 2.85%, the French CAC 40 plunged 1.88% and the German DAX fell 2.33%.

The Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index — often regarded as the key indicator of volatility — has reached heights not seen since the early days of the March 2020 Covid lockdown and is signalling that uncertainty is on the rise.

This is a time when psychology in financial advice has never been more important.

“A lot of people out there are looking for someone to trust in various aspects of their life. Whether it’s politics, finance or sport, there is a desire to trust people,” says 7IM head of equity strategy Ben Kumar.

“But there’s also a massively increased amount of misinformation. ‘Fake news’ wasn’t a term 20 years ago.

“As an adviser, you are the one who is able to cut through the fake news, at least about the markets, so you’ve got a responsibility to do so and to be as engaged in the likely psychology of people as possible.”

Kumar says advisers themselves need to be ready for when client panic sets in, but also should understand that they cannot prepare their clients ahead of time.

The way that clients relate to you is more important than your expertise and your fees

“You can tell them they’ll be scared. You can tell them not to worry. And you can say markets might fall and they’ll go up and down,” he says.

“But it’s a bit like turbulence on a plane. When turbulence hits, your palms are sweaty, you feel nervous, you feel sick, and you can’t do anything about it.

“Artificial intelligence [AI] I isn’t going to help. Robo-advice isn’t going to help. Virtual reality is not going to help. People will be scared because they’re scared, and that is not going to change.”

Self-belief

Dynamic Planner head of psychology and behavioural insights Louis Williams says that, when we think about clients’ psychology, often we focus just on biases or attitudes to risk; but, in fact, a lot of it is about clients’ behaviour and what may happen in the future, and how they will react.

“As much as our attitudes can influence how we may behave in the future, there are many other elements that affect how we actually behave,” he says.

Financial planners are uniquely positioned to help clients with what has been consistently identified as one of the top sources of stress — money

Some traditional theories suggest that the way we feel about something can affect how we intend to behave. A classic example is if we’re trying to change an aspect of our behaviour.

“If you want to give up smoking, for example,” says Williams, “you may have the view that it’s not good for you, and other people may be telling you the same, so you have that social reinforcement.

“But, if you don’t believe in your ability to give it up, if you don’t have self-efficacy and a level of confidence in being able to do it, that influences your behaviour in a stronger way.”

Williams says advisers must help their clients build such confidence in relation to their ability to manage their finances.

You need to keep the right level of information but be able to present it to all of your clients in the most brain-friendly way

“You can be as risk seeking as you like, and have good relationships and good finances, but when it comes to behaviour you need to have self-efficacy.”

He suggests that those with a higher level of self-efficacy are often the ones to seek advice in the first place.

‘Trusted person’

Advertising tycoon David Ogilvy once said: “The problem with people is they don’t think how they feel, they don’t say what they think, and they don’t do what they say.”

Kumar says: “We all know that, when you tell someone what you’re going to do, you don’t necessarily do it. The reason you say you’re going to do it is maybe different from what you actually think. And then you have emotions that come into it.

“As an adviser, there is a real advantage to being a trusted person to whom a client can almost outsource their financial emotions.”

Embracing the psychological aspects of planning will help a financial planner acquire, service and retain clients, but can do so much more

Williams says a challenge for advisers is in reassuring clients that their feelings about a situation are not wrong.

“Sometimes we think it’s wrong to have negative feelings or to feel worried,” he says. “The adviser needs to learn to explain to the client that having those feelings is OK. The challenge then is how do we manage those emotions?”

Williams adds: “It’s important for the adviser to teach the client more about reappraising the situation, focusing on what they can control, trying to reduce the noise and their exposure to the news, because this just fuels some of the people biases.”

One such bias is recency bias, where people base their decisions on what is happening right now, and that affects what they may do in the future.

Williams suggests advisers can help their clients through tough times by working on their own emotional intelligence.

“When you build your emotional intelligence, you’re able to then understand and recognise the client’s emotions when they’re going through those challenging periods.”

For the majority of an adviser’s clients, it is important that the adviser has more than just good communication skills and technical knowledge

He suggests advisers can then use their own emotions and what they have learned to assist the client through those difficulties, helping them regulate and use their emotions in a positive way.

Emotional intelligence has been shown in research to lead to positive outcomes for not just the client but the adviser as well.

Williams adds: “There is research showing that advisers who demonstrate greater levels of empathy and emotional intelligence have more referrals from clients because they provide better outcomes. They often even have lower stress themselves.”

Kumar says an analogy he uses when speaking to advisers is that, if you have a child and your child is scared at night, it is no good saying to them, ‘There are obviously no monsters in the cupboard because monsters don’t exist.’

Instead, what your child needs is a hug and some reassurance, and maybe for you to open the cupboard and shout at the monster.

“You need to be human about it,” says Kumar.

There is a tendency, especially in a knowledge-based business such as financial advice, to lead with competence rather than warmth

In the same way, he says, remembering to be human is important when it comes to the psychology of advice.

This comes into play long before the client and adviser start working together.

Client motivations

Research indicates that people seek financial advice for all sorts of reasons.

Tom Mathar, head of Aegon UK’s Centre for Behavioural Research, says: “When you ask people, even advisers, why people seek advice, there are all sorts of objective, utilitarian reasons that they mention: things like tax planning, retirement planning and estate planning.

“But I would argue that it is the underlying other reasons that are the important ones.”

Mathar cites a book by psychologist Moira Somers, which lists many of the emotional reasons for which people seek financial advice, whether to save time, offload unpleasantries, have someone else to blame or overcome ‘analysis paralysis’ — the inability to make decisions because you’re too busy over-analysing.

“Typically, people don’t want to just accumulate wealth,” says Mathar.

“They want to live a certain lifestyle, and they want to be OK, and they want to know that their kids will be OK.

There is research showing that advisers who demonstrate greater levels of empathy and emotional intelligence have more referrals from clients because they provide better outcomes

“This is why the psychological side of financial advice is so important to acknowledge and consider, because it’s not just about the utility of why you seek financial advice.”

Of course, there are clients who want advice simply on their financial products and nothing else.

But typically, says Mathar, people are looking for more when they seek financial advice; whether it is life related, family related or work related, it is about “addressing deeper needs”.

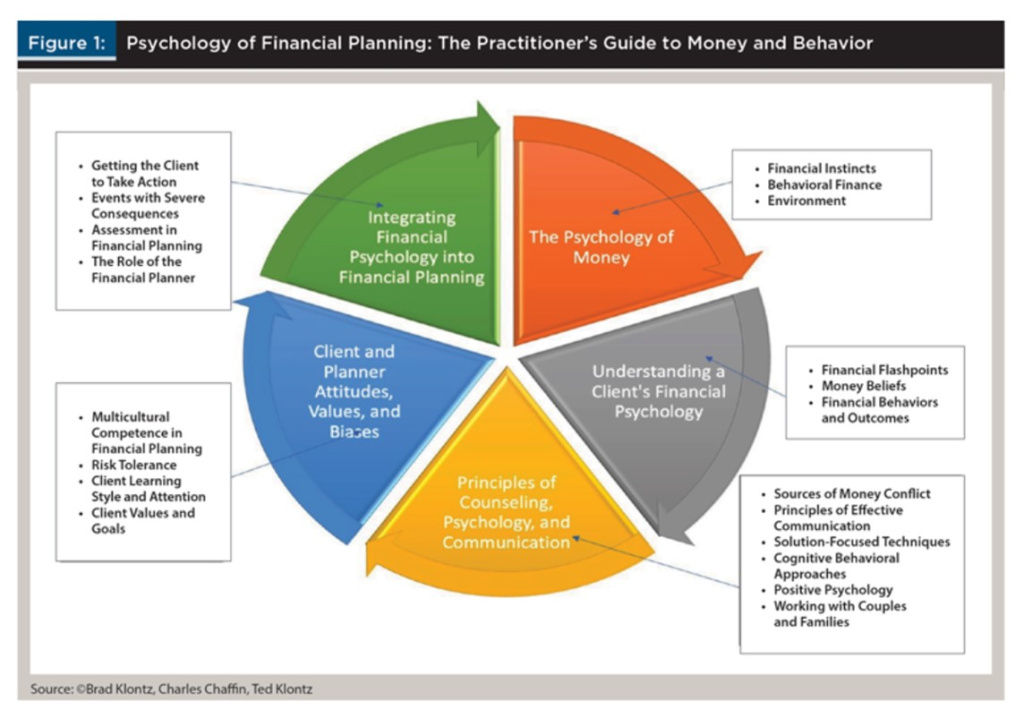

A paper published in the Journal of Financial Planning in the US in January last year suggests that the psychology of financial planning covers much more than cognitive psychology.

It seeks to understand a client’s entire psychology of money, including: upbringing, past experiences, learning style, psychological risk profile, money beliefs, financial behaviour, cultural identity, values, motivation, relationship and family dynamics around money, sources of intrapersonal and interpersonal conflicts around money, and more.

When you build your own emotional intelligence, you’re able to then understand and recognise the client’s emotions when they’re going through those challenging periods

“For the majority of an adviser’s clients, it is important that the adviser has more than just good communication skills and technical knowledge,” says Mathar.

“It is so important for financial advisers to understand the emotional landscape their clients have: their psychographic profile, what motivates them, what impedes them, what keeps them up at night, and all those things.”

Building rapport

Knowing that there are more important considerations for a potential client than just technical knowledge can help advisers with onboarding.

BareRock head of behavioural science and chief experience officer (advisory) Babs Crane suggests that, when interacting with a client — potential or new — advisers should aim to build rapport and approachability.

“That should be the thing you lead with, before you follow it up with demonstrating your competence and giving information,” she says.

There is a tendency, adds Crane, especially in a knowledge-based business such as financial advice, to lead with competence rather than warmth.

However, she argues, the rapport-building phase has been shown in several psychological tests to be the most important thing when building trust with clients.

As an adviser, there is a real advantage to being a trusted person to whom a client can almost outsource their financial emotions

Williams says there has been a lot of research on the factors that are important when a client decides to work with an adviser.

“The way they relate to you and build that emotional relationship with you is more important than your expertise and your fees and things like that,” he says.

When a client has come on board, how you then engage with them remains important, and the financial services sector is notoriously jargon heavy.

“The more we can simplify the language in our profession, and reduce jargon so as to demystify personal finance, the better,” says Cathy Brennan, a senior financial planner at Knightsbridge Wealth Management who also owns a financial coaching practice.

Tailored approach

But Crane warns that advisers should not be tempted to “dumb things down” too much for all clients, but should present things in a digestible way.

“There are differences between everybody,” she says.

You can be as risk seeking as you like, and have good relationships and good finances, but when it comes to behaviour you need to have self-efficacy

“There are people who have a really high need for cognition, who want to learn about things and understand things — that makes them feel a lot better.

“Then there are people with very low needs for cognition. They just want the really basic information and that’s enough for them.”

Crane adds: “You need to keep the right level of information but be able to present it to all of your clients in the most brain-friendly way.”

Some advisers are resistant to talking about the importance of psychology and behavioural analysis in advice.

The Journal of Financial Planning paper suggests that the integration of the psychology of financial planning into the financial planning knowledge base offers an opportunity to better understand and serve clients.

A lot of people out there are looking for someone to trust in various aspects of their life

“A financial planner’s work is much more than just giving a client financial advice and managing a client’s investments,” it says. “Financial planners are uniquely positioned to help clients with what has been consistently identified as one of the top sources of stress — money.

“Embracing the psychological aspects of financial planning will help a financial planner acquire, service and retain clients, but can do so much more.

“The psychology of financial planning will equip our profession with the theory and tools we need to help clients reach their financial goals, improve their relationships and increase their financial and life satisfaction, and help improve the financial health of society at large.”

Commercial need

Many commentators believe there is a commercial need to start embracing the psychology of advice.

“There is a lot of automation happening,” says Mathar.

“DIY is on the rise when you look at the DFMs [discretionary fund managers]. And who knows what AI’s next move is in the industry?”

The adviser needs to learn to explain that having negative feelings is OK

This, he argues, means that a lot of the traditional skills of a financial adviser, such as stockpicking and risk profiling, have become automated.

Kumar echoes this.

“In the world we live in now, most investment propositions are centralised and broadly sensible. There is also a framework in place for risk rating clients. So, in most cases, financial advice comes down to the psychology.

“People don’t know what it’s like to see markets go up and down until they’re invested.

“So, the adviser needs to be like a psychologist and therapist, and prepare people for what’s going to be a really difficult time in their life.”

Lessons from the US

Interestingly, when doing my initial research for this feature, I noticed how many more articles on the topic of financial psychology seemed to appear on US websites than on UK sites.

In 2021, the psychology of financial planning was introduced as one of the eight principal knowledge topics recognised by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards (CFP Board) in the US. It began being tested on the Certified Financial Planner (CFP) exam in March 2022.

The topic is designed to help financial advisers improve their understanding of the relationship that clients have with their finances. It also looks at why it is important for advisers to have deeper conversations to help clients make future financial decisions.

This is beginning to be spoken about more in the UK too, but as a side note rather than an integral aspect of financial planning.

Perhaps the bigger focus on financial psychology in the US is because of the ‘American spirit’ of embracing working on yourself and being the best you can be

“There are quite a few established players in the US,” says Tom Mathar, head of Aegon UK’s Centre for Behavioural Research. “But they are all finding it relatively hard to get a foot in the door in the UK.

“This is despite the fact that, in the UK, the regulatory context should pave the way much more for it. Since the Retail Distribution Review, the sector has focused on long-term relationships with clients and it’s less about selling for commission.”

Mathar wonders if the bigger focus on financial psychology in the US is because of the “American spirit” of embracing working on yourself and being the best you can be. Or maybe it is merely that the financial advice sector is so much larger in the US, so it appears that more advisers are adopting the strategy.

Either way, by observing examples of what can be done in this area from across the pond, and examining the numerous psychological studies to come out of the US, UK-based advisers have interesting food for thought.

Source: Journal of Financial Planning: January 2023

Source: Journal of Financial Planning: January 2023

This article featured in the September 2024 edition of Money Marketing.

If you would like to subscribe to the monthly magazine, please click here.

LV has experience and, I think, qualifications in seiko stuff – ‘Someday, all advisers will think this way’ A classic and old watch advert for the brand… not that LV is selling watches!

The article is beyond the time I have to read in full, yet, two things early on caught my attention…

Why not sell your Lloyds Bank shares and immediately rebuy – you have losses to carry forward for years against gains as they always rise in the end, + you effectively hugely increase your yield;

I used to fly a lot – CH 15x + LA 12-14x a year – a sage Stewardess gave me irrepressable wisdom – ‘If your number is up it’s up… but you just have to hope the pilots’ numbers are OK’! Point! Why do airline seats face forward, surely backwards would be safer – non?

Time is pressing… now, where’s my Gibbons Decline & Fall… ZZZzzzz…

Seriously comprehensive article – and must be good to keep my attention span hooked the whole way through. It actually blew my mind a bit