One of my first investment learnings in the hazy years of university was around the haloed small-cap effect.

Small caps are perceived as inherently riskier than their larger counterparts. A combination of variable growth rates, lower liquidity, substantially reduced sell-side coverage (all versus large or mega caps) and reduced access to capital markets should lead to greater inefficiencies and require an extra premium to own.

Over time, this premium should lead to higher expected returns. So, why have small-cap returns been so lacklustre in recent years?

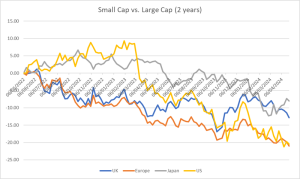

Indeed in most major markets, the past few years have seen small-cap returns trounced by their larger peers. Smaller companies on aggregate are more economically sensitive than larger multinationals, therefore a difficult economic environment can lead to meek returns.

Source: Lipper for Investment Management, Total Return, GBP as as 30 April 2024.

Despite the US economy continuing to grow strongly, its small-cap market has had the weakest returns, relative to large cap, across major markets.

It’s certainly plausible that smaller companies have more of their debt as floating rate, meaning greater sensitivity to higher borrowing costs against the backdrop of the fastest interest rate hiking cycle for a generation. They may now face substantially higher interest rate bills, depressing profitability and dampening investor returns.

The most obvious reason underpinning the relative performance is the enormous, but somewhat historically anomalous, growth rates by mega-cap technology companies. Particularly in the US, these companies are continuing to scale in a relatively asset-light manner compared to any point in mega-cap history.

If small-cap earnings are unable to keep pace, let alone grow at a faster rate, then investors are unlikely to take the added ‘risk’ within them. In addition, the deep pockets of mega caps mean they are able to acquire companies much earlier in their lifecycle to add additional growth to their own business.

Eventually, the adoption of technology could become a double-edged sword. NVIDIA, for example, listed with a market cap of less than $2bn in 1999 – today it is $2.3tn. It would be unreasonable to suggest this growth cannot occur again. Who knows whether artificial intelligence becomes one of market’s great levellers and enables rapid growth in smaller companies harnessing its potential.

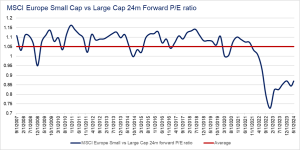

The effect is more widespread than the US, however. European small cap, for instance, now trades at close to its most meaningful discount relative to large-cap peers, on a forward multiple basis, since pre-global financial crisis.

Source: Bloomberg as at 30 April 2024

Markets are said to be more inefficient the further down the market cap scale you go, and recent M&A take-out premiums are certainly backing this up.

In a recent discussion, Gresham House Smaller Companies fund manager Ken Wotton stated one fifth of his portfolio by name has been acquired since, at an average premium of 41%. Further still, some two thirds of company takeouts in UK markets have occurred beneath £500m market cap.

We’d no sooner finished our conversation when another of his top 10 positions had been taken private – Keywords Studios – at a chunky 75% premium. These market inefficiencies are being recognised by others, private or otherwise, and it’s odd they should be valuing companies so differently, implying the discount to small cap is unwarranted.

One risk to the market is that the highest quality smaller companies may no longer require a public listing to continue their growth trajectory, with deep pockets of private markets able to fund companies for longer.

Data from S&P Global reveals the average IPOs in 2021 listed 2-3x larger than 2001, even adjusted for inflation. However, the disastrous performance of post-IPO companies which listed since 2020 mean investors take a much more scrutinous approach to the perceived ‘quality’ private-for-longer companies. The Renaissance IPO Index, an index which tracks the performance of recent US IPOs, has fallen 37% since December 2020, or 91% relative versus S&P 500.

Rather than a blanket approach to small-cap risk and return, we prefer the edge fundamental equity managers still retain in this part of the market. The risks in small cap may be different – larger incumbents may be more agile than ever – but the same technology enabling this growth could well turbocharge their smaller equivalents, perhaps to an even greater extent.

If we are able to buy into multi-year relative low valuations, with skilled active small cap managers at the helm, all while private equity pay materially higher prices, then we’re comfortable being patient investors.

Catalysts include either an easier monetary backdrop or even just a mild growth slowdown within mega caps. History suggests the snap back into small caps could be rapid – blink and you’ll miss it.

Adam Norris is portfolio manager at Columbia Threadneedle Investments

Comments